Inside Bashar Assad’s detention centers, where death was the least bad thing

Handcuffed and squatting on the floor, Abdullah Zahra watched in horror as smoke rose from his cellmate’s flesh while torturers applied electric shocks. Then it was Zahra’s turn. The 20-year-old university student was hanged by his wrists until his toes barely touched the ground. For two hours, he endured electrocution and beatings, as his captors forced his father to watch, mocking him over his son’s suffering.� This was in 2012, during the height of then-President Bashar Assad’s brutal crackdown on protests against his regime. The entire Syrian security apparatus had been deployed to crush dissent. With Assad’s fall a month ago, the machinery of death he commanded is now being revealed to the world. According to activists, rights groups, and former detainees, the system was systematic and meticulously organized. Over the years, it grew into more than 100 detention facilities where torture, brutality, sexual violence, and mass executions were rampant. Even Assad’s own soldiers were not spared, and young men and women were detained for merely living in districts where protests took place.� For over a decade, tens of thousands disappeared, leaving a blanket of fear that silenced Syrian society. Families dared not speak of loved ones who had vanished, fearing that they too might be reported to the security agencies.� Now, with Assad ousted, the silence has been shattered. The insurgents who swept him from power have opened detention facilities, releasing prisoners and exposing the horrors within. Crowds have swarmed these facilities, searching for answers, the bodies of loved ones, and ways to heal. The Associated Press visited seven such facilities in Damascus and interviewed nine former detainees, some of whom were released on Dec. 8, the day Assad was deposed. While some details of their accounts could not be independently verified, they align with past reports from former prisoners documented by human rights organizations. Days after Assad’s fall, Zahra, now 33, returned to Branch 215, a notorious detention facility run by military intelligence in Damascus where he had been held for two months. In an underground dungeon, Zahra stepped into the windowless, 4-by-4-meter (yard) cell where he says he was packed with 100 other inmates. Each man was allocated only a single floor tile to squat on. “When ventilators weren’t running—either intentionally or due to power failures—some suffocated,” Zahra said. “Men went mad; torture wounds festered. When a cellmate died, his body was stowed next to the cell’s toilet until jailers came to collect the corpses.”� “Death was the least bad thing,” Zahra said. “We reached a place where death was easier than staying here for one minute.”

Handcuffed and squatting on the floor, Abdullah Zahra watched in horror as smoke rose from his cellmate’s flesh while torturers applied electric shocks. Then it was Zahra’s turn. The 20-year-old university student was hanged by his wrists until his toes barely touched the ground. For two hours, he endured electrocution and beatings, as his captors forced his father to watch, mocking him over his son’s suffering.�

This was in 2012, during the height of then-President Bashar Assad’s brutal crackdown on protests against his regime. The entire Syrian security apparatus had been deployed to crush dissent. With Assad’s fall a month ago, the machinery of death he commanded is now being revealed to the world.

According to activists, rights groups, and former detainees, the system was systematic and meticulously organized. Over the years, it grew into more than 100 detention facilities where torture, brutality, sexual violence, and mass executions were rampant. Even Assad’s own soldiers were not spared, and young men and women were detained for merely living in districts where protests took place.�

For over a decade, tens of thousands disappeared, leaving a blanket of fear that silenced Syrian society. Families dared not speak of loved ones who had vanished, fearing that they too might be reported to the security agencies.�

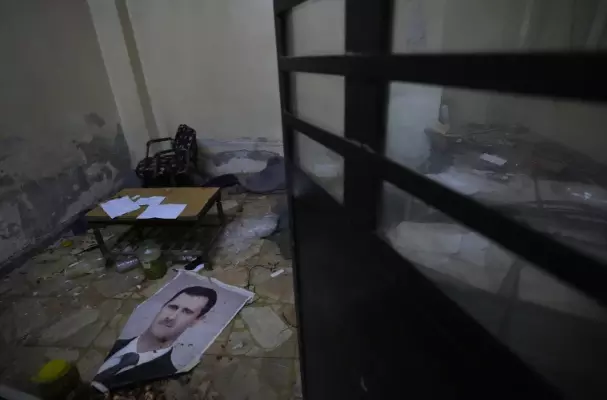

Now, with Assad ousted, the silence has been shattered. The insurgents who swept him from power have opened detention facilities, releasing prisoners and exposing the horrors within. Crowds have swarmed these facilities, searching for answers, the bodies of loved ones, and ways to heal.

The Associated Press visited seven such facilities in Damascus and interviewed nine former detainees, some of whom were released on Dec. 8, the day Assad was deposed. While some details of their accounts could not be independently verified, they align with past reports from former prisoners documented by human rights organizations. Days after Assad’s fall, Zahra, now 33, returned to Branch 215, a notorious detention facility run by military intelligence in Damascus where he had been held for two months.

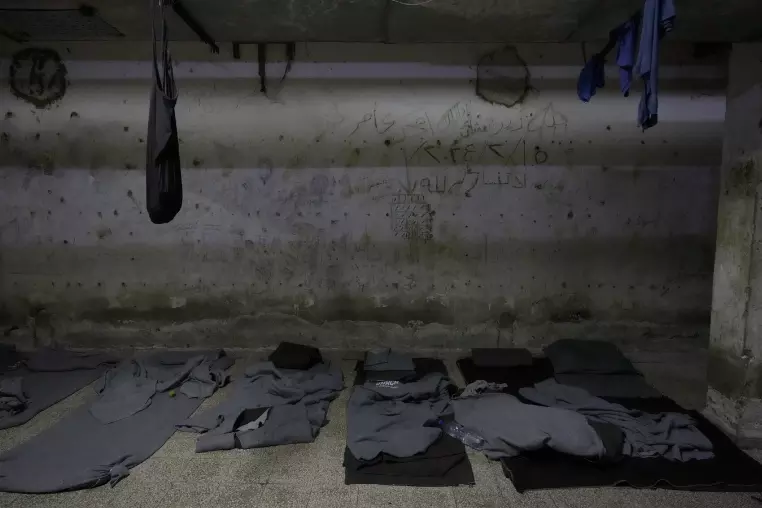

In an underground dungeon, Zahra stepped into the windowless, 4-by-4-meter (yard) cell where he says he was packed with 100 other inmates. Each man was allocated only a single floor tile to squat on. “When ventilators weren’t running—either intentionally or due to power failures—some suffocated,” Zahra said. “Men went mad; torture wounds festered. When a cellmate died, his body was stowed next to the cell’s toilet until jailers came to collect the corpses.”�

“Death was the least bad thing,” Zahra said. “We reached a place where death was easier than staying here for one minute.”