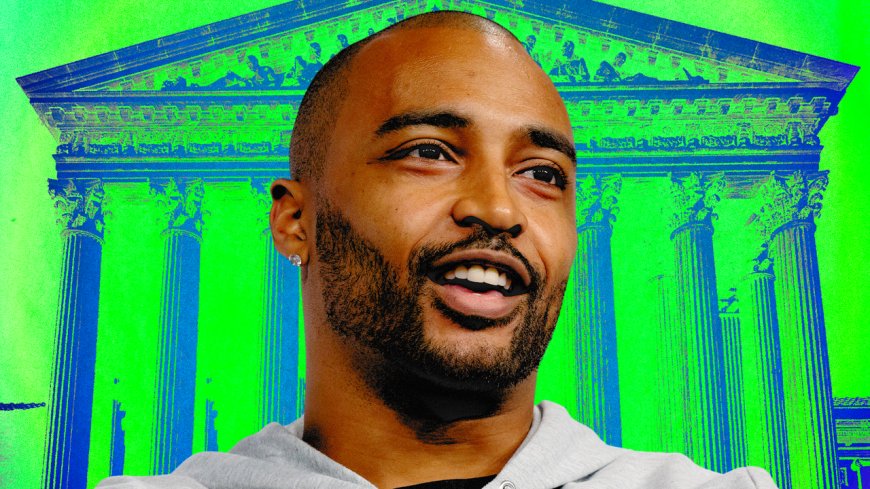

Doug Baldwin Jr. Used to Catch Passes for the Seahawks. Now He's Helping Free People From Prison

GQ SportsSince 2022, the Seattle fan favorite has served on Washington's Clemency and Pardons Board—part of a longstanding commitment to criminal justice reform, and an essential part of his post-playing journey.By Benjamin CassidyNovember 15, 2024Photographs: Getty Images; Collage: Gabe ConteSave this storySaveSave this storySaveEarlier this season, CBS cameras caught Marshawn Lynch giving new Seattle Seahawks coach Mike Macdonald a mid-game massage. The viral moment during the team’s season-opener against the Broncos signaled both Beast Mode’s apparently vast sideline latitude and his support for the man succeeding Pete Carroll.Less seen that day was a conversation on the field before the game between Lynch, MacDonald, and Doug Baldwin Jr., the former Pro Bowl Seahawks receiver equally devastating in route trees and on the microphone during the franchise’s golden age. He later offered his own endorsement of Macdonald.“It is a new era in Seattle,” Baldwin posted on X. “Mike is not only a good coach but more importantly, he’s a good leader for those young men. That makes me happy. The @Seahawks got a good one.”The Stanford alum’s typically soulful words still hold significant sway with the 12s. And though he’s been far less visible in retirement than Lynch, who’s kept busy starring in commercials and movies, Baldwin has embarked on perhaps an even more unorthodox—and possibly more influential—post-playing career.A few days after his visit to Lumen Field, Baldwin called into a meeting of a little-known government commission that makes life-altering decisions. Every quarter, Washington’s five-member Clemency and Pardons Board—of which Baldwin has been a member since 2022—hears petitions for commutation of sentences and pardons for people who’ve often spent decades in prison for everything from gun possession to murder. On these quarterly video conferences, Baldwin and his much less famous colleagues listen to hours of testimony from these petitioners, as well as from friends, family members, and attorneys on both sides of a case. After each hearing, the board members vote on whether “extraordinary circumstances” merit granting clemency, a recommendation the governor adopts almost every time.Baldwin, the son of a law enforcement officer, has long been interested in using his platform to work through the political issues that matter to him. As a player, he announced that the Seahawks would link arms during the national anthem and advocated for a bill that would train police officers in de-escalation. His participation on the clemency board is an opportunity to continue his work on systemic justice reform, and part of Baldwin’s broader mission to find purpose since retiring in 2019. That includes his day-to-day responsibilities as the founder of the Family First Community Center, as CEO of social impact investment firm Vault89, and as a husband and father to three girls. He knows the fleeting playing careers of football players don’t often prepare them for what comes next, something he reflected on during his visit with Macdonald that day. “Maybe even two years ago, stepping on that field that would have been all about me and all about that feeling of going out and combating on the field and all that adrenaline,” Baldwin tells GQ. “But now I’m stepping on that field and recognizing, man, all of these young men have had a journey to get here, and then when they're done with this field, they have a journey afterwards. And I’ve seen the unhealthy ones, and I’ve seen some healthy, but they all have a journey.”During a video call after the most recent hearings of the Clemency and Pardons Board, Baldwin spoke about his own journey from being “Angry Doug Baldwin” in the NFL to helping free people from prison. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.You were known for your intensity on the field, and you’ve mentioned in other interviews that you struggled with the transition to your post-playing career. How did you struggle, exactly?It was related to identity. I had been playing football since I was six years old, and I had been celebrated for my performance on that field since I was seven years old. So it became kind of a lifeline for me. And when I did not have that, I felt misplaced. I felt lost in the world. I didn’t know where I stood because nobody was giving me the affirmation of, like, “Oh, yeah, you’re doing a good job right now.”So not having that, on top of my first daughter being born, being two and a half years into marriage…there’s so much non-instant gratification or instant affirmation when it comes to being married and having children that I think that also added to the challenge. But I also think it was a benefit to me, because I had something else to pour into. Something else that was—I don’t want to say distracting my mind from the negativity, but was pulling my mind in a different direction.What advice had you received about how to handle retirement?Most people that I spoke to sai

Earlier this season, CBS cameras caught Marshawn Lynch giving new Seattle Seahawks coach Mike Macdonald a mid-game massage. The viral moment during the team’s season-opener against the Broncos signaled both Beast Mode’s apparently vast sideline latitude and his support for the man succeeding Pete Carroll.

Less seen that day was a conversation on the field before the game between Lynch, MacDonald, and Doug Baldwin Jr., the former Pro Bowl Seahawks receiver equally devastating in route trees and on the microphone during the franchise’s golden age. He later offered his own endorsement of Macdonald.

“It is a new era in Seattle,” Baldwin posted on X. “Mike is not only a good coach but more importantly, he’s a good leader for those young men. That makes me happy. The @Seahawks got a good one.”

The Stanford alum’s typically soulful words still hold significant sway with the 12s. And though he’s been far less visible in retirement than Lynch, who’s kept busy starring in commercials and movies, Baldwin has embarked on perhaps an even more unorthodox—and possibly more influential—post-playing career.

A few days after his visit to Lumen Field, Baldwin called into a meeting of a little-known government commission that makes life-altering decisions. Every quarter, Washington’s five-member Clemency and Pardons Board—of which Baldwin has been a member since 2022—hears petitions for commutation of sentences and pardons for people who’ve often spent decades in prison for everything from gun possession to murder. On these quarterly video conferences, Baldwin and his much less famous colleagues listen to hours of testimony from these petitioners, as well as from friends, family members, and attorneys on both sides of a case. After each hearing, the board members vote on whether “extraordinary circumstances” merit granting clemency, a recommendation the governor adopts almost every time.

Baldwin, the son of a law enforcement officer, has long been interested in using his platform to work through the political issues that matter to him. As a player, he announced that the Seahawks would link arms during the national anthem and advocated for a bill that would train police officers in de-escalation. His participation on the clemency board is an opportunity to continue his work on systemic justice reform, and part of Baldwin’s broader mission to find purpose since retiring in 2019. That includes his day-to-day responsibilities as the founder of the Family First Community Center, as CEO of social impact investment firm Vault89, and as a husband and father to three girls. He knows the fleeting playing careers of football players don’t often prepare them for what comes next, something he reflected on during his visit with Macdonald that day. “Maybe even two years ago, stepping on that field that would have been all about me and all about that feeling of going out and combating on the field and all that adrenaline,” Baldwin tells GQ. “But now I’m stepping on that field and recognizing, man, all of these young men have had a journey to get here, and then when they're done with this field, they have a journey afterwards. And I’ve seen the unhealthy ones, and I’ve seen some healthy, but they all have a journey.”

During a video call after the most recent hearings of the Clemency and Pardons Board, Baldwin spoke about his own journey from being “Angry Doug Baldwin” in the NFL to helping free people from prison. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

It was related to identity. I had been playing football since I was six years old, and I had been celebrated for my performance on that field since I was seven years old. So it became kind of a lifeline for me. And when I did not have that, I felt misplaced. I felt lost in the world. I didn’t know where I stood because nobody was giving me the affirmation of, like, “Oh, yeah, you’re doing a good job right now.”

So not having that, on top of my first daughter being born, being two and a half years into marriage…there’s so much non-instant gratification or instant affirmation when it comes to being married and having children that I think that also added to the challenge. But I also think it was a benefit to me, because I had something else to pour into. Something else that was—I don’t want to say distracting my mind from the negativity, but was pulling my mind in a different direction.

Most people that I spoke to said, “Just know it’s going to be hard.” They didn’t really have more than that. I did have one former teammate who was in the locker room before one of our games, and my mind was already like, Man, this time is coming at some point. So I just asked him, “Hey, was retirement hard for you?” And he shook his head no. That kind of shook me too, like, Dang, okay, so everybody else is telling me it’s hard. He’s saying it’s not hard.

What I learned from that was he had other things planned and ready for his retirement. He was able to pour himself into other things and find fulfillment and affirmation, whereas I was just like, “Okay, football’s up. I don’t know what’s next.” Just the nature of how I was, I couldn’t expend any energy on anything else other than football at the time, so I wasn’t as well-rounded as I would have liked to have been leaving the game.

I would say probably a year and a half, two years ago. It could even be less, to be completely honest—not necessarily physically, but emotionally and mentally and even spiritually, to some degree. I didn’t find this higher level of balance until probably less than a year ago.

I was doing some work on some other initiatives in the state of Washington, and one of the contacts that I was working with, he was the liaison between the governor’s office and myself. He was like, “Hey, what do you think about this? Are you interested in this?” And quite honestly, when I looked into it, I felt called to it. I felt really strongly compelled to join it.

It’s a great question, and one that I don’t know if I have a good answer to, but this is how I will try to answer this: My faith has been a very strong component of how I’ve navigated the world and how I’ve felt sane in a lot of ways, and this is no different. So when it comes to—it’s hard for me even to say criminal justice or justice, because it’s an inherently flawed system, and sometimes justice doesn’t prevail, even in the system. I think I’m seeing that in some of these cases. But what I would say is that I look at the people that come before our board, and they’re just like me. They’re just human beings who are flawed ... They come from really challenging backgrounds, and they may or may not have had the support in ways that would effectuate a positive change in their life, to be able to balance or counteract the challenges that they’re facing. So I look at them with a ton of grace.

And I think that’s always been the case for me. My dad being a law enforcement officer, and he carried himself in that way, too. Like, yeah, I am supposed to be upholding the law, but I also recognize that none of us are upholding the law. We’re all flawed in a lot of ways. So I guess I innately and subconsciously carry that demeanor.

The first set of hearings, they were all like aggravated murder cases. I still don’t even have the words to articulate how I navigated those first hearings. But I would like to say my role on this board is that I have a deep connection with my faith in regards to grace and forgiveness. And I think it does bode well in those hearings. Because to your point, we have the legalese, we have the experts, we have the people who have all the experience in the world, but I’m able to bring a different perspective at times. And in order for us to be a well-rounded board, I think all of those perspectives are necessary.

We get hundreds of pages of content and materials for each case. Now, candidly, I don’t go through every page. It’s just impossible to do so, but I know what my other board members are going to be looking for, so then I spend my time on things that they may not be spending as much time on.

There was one case. It was an aggravated rape, and I can’t remember the specific outcome of it, because it’s really hard for me—I don’t want to hold on to those things. I’m in it, and then I’m out of it. But in the petition form to us, one of the questions was, “Was the victim injured?” And [the petitioner] put “no.” So I asked him, “Can you help me understand why you put ‘no’ for this answer?” And I didn’t like the answer. I didn’t like the answer from the lawyer, and I didn’t like the answer from the petitioner. And part of our evaluation is, does this person come to the board remorseful and fully understanding of what they did? So from all the materials that I read up to that point, I didn’t feel like I was getting the remorse.

I don’t go in with a decision. I go in and I’m expecting for this person to tell me one way or the other; with the questions that we ask, they need to tell me one way or the other. So when I asked that question, I wasn’t leaning toward a yes—I still just didn’t know. And that kind of sent me. It wouldn’t have been the right decision to vote for a commutation because of the answer and the response that I got to that one question, on top of all the rest of the materials.

Yeah. It doesn’t have a definition of what extraordinary is.

I say it in my introduction [during the meetings]: I recognize just how weighted these decisions are, not only for the petitioner and their family, but also for everybody who’s watching, for the community at large, for any of the petitioners that come after this person, and also any board members that come after me. It’s a responsibility that I don’t take lightly, and I guess how I’ve tried to approach stewarding this responsibility is making sure that I am grounded in my own health and wellbeing and being connected with my spirituality and humanity, so that when I show up to these hearings, that I am the most connected and grounded version of myself so that I can make the best decision.

It comes from my faith, and the belief that we’re all redeemable. None of us are a lost cause. All of us can be reached. I do believe that we’re all connected. The oxygen that I breathe, I breathe that back out, and somebody else is going to breathe that in. We’re all connected. So if I’m so harsh in my quote-unquote judgment of another human being, that judgment is just going to come back to me. So I would much rather give grace, and lean on the side of forgiveness, rather than just being harsh and not giving grace or not being forgiving, especially in these situations where I genuinely feel like this person is rehabilitated and has been humbled through the experience in the rehabilitation process.

But there’s no clear definition of extraordinary, so it’s really hard to make a decision in those situations. If my heart is telling me that this person is humble, has been rehabilitated, then I would rather lean on the side of giving grace than not.

It’s a tall order for the victim or the victim’s family to get to a place where they can have forgiveness and grace for the perpetrator. I recognize that just on the surface level, both as somebody who is a participant of this board, but also somebody who has been a victim of, you know, things, I don’t expect the victims or the victim’s family to have grace or forgiveness for the perpetrator. And the things that they write—if I’m being honest, a lot of these letters are very similar: This person took my brother's life or my mother’s life, or did the unimaginable to a child or to somebody else. It’s all the same. “We can’t let this person in society.” Whatever it is, right? The experience is: This is not a good human being. So as much as that does weigh on my conscience, I fundamentally disagree that the person is not redeemable.

I think the altruistic intent of the justice system—quote-unquote justice system—is to take folks who have challenges in the real world and to rehabilitate them so they can then acclimate back to the real world in a healthy and productive manner. At least, that’s my understanding. I could be wrong there. So I can understand that somebody who’s going through a traumatic event may not be able to give grace and forgiveness to somebody who, from an outsider’s perspective, may have gone through the rehabilitation process and may, in my opinion, be genuinely rehabilitated.

So I genuinely don’t expect the victim or the victim’s family to have remorse, but I do think in the cases where they do give grace and have remorse, that is profoundly extraordinary. And so those are—I don't want to say those are easier cases, but it doesn’t come with as much weight as the ones where there’s an opposing view from the victim’s side. I take all of it into account. However, my belief is that what is going to heal the whole narrative and the whole story is to give grace and forgiveness when there is space to give it, when the recipient is ready to receive it. And that’s not on me. That’s on them.

Now as a father and as a husband who’s been away from the game with enough time to reflect on that entire experience, one of the things that I walked away with was realizing just how all of the coaches that I’ve been around have impacted my life. My dad, he’s a flawed human being. I love him. I love him to death. We got a great relationship now; we didn’t have so much of a great relationship when I was younger. But I can imagine that a lot of those young men, they're growing up with a wide array of modeling of what a man and what a father should be, and coaches play such a pivotal and vital role in young men’s lives because, a lot of the time, they are that role model. They are that example. And I recognize just how important that is and how impactful it’s been for me.

So my conversation with Mike on the field—that was my first time actually meeting him face-to-face and having a conversation with him. But I’ve heard lots of things about who he is and what he represents. So I had a good picture of who he was and what I could say to him. And I just told him, Hey, I know you know this as a man of faith, but you play such a pivotal role in these young men’s lives. And I’m just encouraging you to recognize that.

If you’re asking me, how do you be a role model, or support those other folks who are going through those journeys? I don’t know. I really don’t. But what I believe wholeheartedly is that if I wake up every day with the motivation and intent to be the best husband, the best father, the best man that I can possibly be, that’s all I can do. And whatever comes of that, whatever happens because of that, will be an example for the person who’s ready to receive that example.