How ‘Lost Notes: Groupies’ Unearthed an Alternate History of ’70s Rock

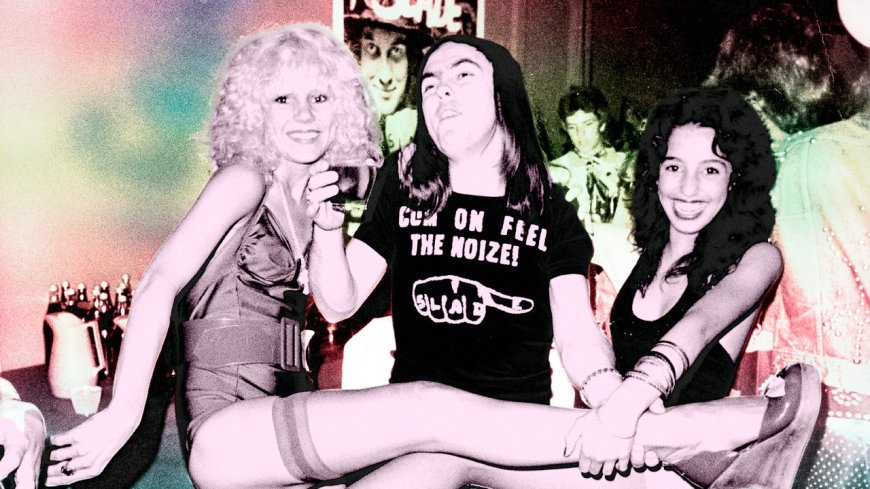

CultureTalking with Dylan Tupper Rupert and Jessica Hopper, whose eight-episode podcast series tells the story of the Sunset Strip scene through the eyes of the so-called “groupies” who defined it.By Paula MejíaNovember 8, 2024Photograph: Getty Images; Collage: Gabe ConteSave this storySaveSave this storySaveHed: The duo behind the Sunset Strip ‘Groupies’ podcast on “putting together pieces of rock history that have never existed”Dylan Tupper Rupert and Jessica Hopper can’t remember when they first became aware of groupies. Rupert is a writer and podcast producer who got involved in the Seattle music scene as a teenager in the early aughts; Hopper, an author and docuseries producer who came of age in Minneapolis’s late 1980s-early 1990s punk community. They’d both heard stories about young women who moved through the glam and punk scenes that coalesced along LA’s Sunset Strip in decades past—about scene queens like Lori Mattix and Sable Starr, who became iconic for hitting buzzy clubs like the Whisky a Go Go in the company of rock stars. But to both Rupert and Hopper, most of those stories always felt incomplete.Over the years, some of these women have recalled the heyday of the Strip in their own words—including Pamela Des Barres, who published the bestselling memoir I’m With the Band in 1987. But historically, groupies have still been defined largely by their proximity to guitar-wielding men like Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck. In recent years—particularly in the wake of the broader #MeToo movement, and accusations of sexual misconduct leveled against male fixtures of the Sunset Strip scene like KROQ DJ Rodney Bingenheimer and the late Runaways manager/producer Kim Fowley— there’s been an overdue reckoning writ large concerning that era. That extends to the power imbalances that existed between the young women in the scene who self-identified as groupies and the significantly older rock personalities they associated with, including the likes of Page and Iggy Pop. But these women have rarely been treated as central figures in their own narratives. As Hopper puts it: “For a long time people would just dismiss groupiedom or groupies, or this time [period], as literally too complicated to think about.”In their new podcast Groupies: Women of the Sunset Strip, From the Pill to Punk, Hopper (who executive produced and co-wrote the series) and Rupert, its host and co-writer, steer straight into those complexities. The show traces the intersecting lives of several women who became pivotal to the Sunset Strip’s late 1960s and 1970s scenes —including Mattix, Des Barres, the Whisky a Go Go’s Dee Dee Keel, and Morgana Welch—and unpacks the sociopolitical forces that shaped their moment. Over eight episodes, the fifth of which debuted earlier this week, Groupies tells a wild yet nuanced story about how its subjects became part of rock and roll myth. In their own words, the show’s subjects detail the ambitions, perspectives and life circumstances that led them to the heart of L.A.’s rock scene—and their indelible effect on the music and the culture surrounding it.GQ spoke with Rupert and Hopper about how the podcast came together, and the untold stories that emerged from their years-long exploration of groupie culture. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.GQ: Tell me about how you started conceptualizing this idea. When did you know that there was a bigger story you wanted to tell about groupies?Jessica Hopper: I think we were talking about big ideas about groupies…maybe wanting to know more about Sable [Starr] and Lori [Mattix]? I remember I was sitting in that hammock at that Airbnb in Silverlake…Dylan Tupper Rupert: Oh yeah.JH: And I said, “I think we gotta make something out of this.” And we were like, “Is it a book? Is this a TV series? Is this a documentary?” And I don't ever think until we were really both a little bit more ensconced in the world of podcasts did we think, “It's a podcast.” I mean, we baked this idea for solid couple of years: getting together materials, trying to talk about what we were finding in other histories, other big holes. And just thinking about: “what was really the best way to tell this story?” We eventually landed on [the idea that] it needs to be a podcast. We want to hear their voices. We want to hear them tell their story. And so I think the idea of moving beyond a book or something happened once we established, like, “Who are they now?”DTR: I think a big reason we decided on the podcast treatment was, like Jessica said, hearing the stories. That's what they have, that's what they were able to take away from this time. They didn't become rich and famous. Pamela [Des Barres] became a best-selling author, but she's not living in luxury by any means. And so they came away with this richness of story that we could best tell over, I guess, seven-ish total hours of documentary versus trying to do a 90-minute feature doc or something. We figured out that we needed to have a len

Hed: The duo behind the Sunset Strip ‘Groupies’ podcast on “putting together pieces of rock history that have never existed”

Dylan Tupper Rupert and Jessica Hopper can’t remember when they first became aware of groupies. Rupert is a writer and podcast producer who got involved in the Seattle music scene as a teenager in the early aughts; Hopper, an author and docuseries producer who came of age in Minneapolis’s late 1980s-early 1990s punk community. They’d both heard stories about young women who moved through the glam and punk scenes that coalesced along LA’s Sunset Strip in decades past—about scene queens like Lori Mattix and Sable Starr, who became iconic for hitting buzzy clubs like the Whisky a Go Go in the company of rock stars. But to both Rupert and Hopper, most of those stories always felt incomplete.

Over the years, some of these women have recalled the heyday of the Strip in their own words—including Pamela Des Barres, who published the bestselling memoir I’m With the Band in 1987. But historically, groupies have still been defined largely by their proximity to guitar-wielding men like Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck. In recent years—particularly in the wake of the broader #MeToo movement, and accusations of sexual misconduct leveled against male fixtures of the Sunset Strip scene like KROQ DJ Rodney Bingenheimer and the late Runaways manager/producer Kim Fowley— there’s been an overdue reckoning writ large concerning that era. That extends to the power imbalances that existed between the young women in the scene who self-identified as groupies and the significantly older rock personalities they associated with, including the likes of Page and Iggy Pop. But these women have rarely been treated as central figures in their own narratives. As Hopper puts it: “For a long time people would just dismiss groupiedom or groupies, or this time [period], as literally too complicated to think about.”

In their new podcast Groupies: Women of the Sunset Strip, From the Pill to Punk, Hopper (who executive produced and co-wrote the series) and Rupert, its host and co-writer, steer straight into those complexities. The show traces the intersecting lives of several women who became pivotal to the Sunset Strip’s late 1960s and 1970s scenes —including Mattix, Des Barres, the Whisky a Go Go’s Dee Dee Keel, and Morgana Welch—and unpacks the sociopolitical forces that shaped their moment. Over eight episodes, the fifth of which debuted earlier this week, Groupies tells a wild yet nuanced story about how its subjects became part of rock and roll myth. In their own words, the show’s subjects detail the ambitions, perspectives and life circumstances that led them to the heart of L.A.’s rock scene—and their indelible effect on the music and the culture surrounding it.

GQ spoke with Rupert and Hopper about how the podcast came together, and the untold stories that emerged from their years-long exploration of groupie culture. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

GQ: Tell me about how you started conceptualizing this idea. When did you know that there was a bigger story you wanted to tell about groupies?

Jessica Hopper: I think we were talking about big ideas about groupies…maybe wanting to know more about Sable [Starr] and Lori [Mattix]? I remember I was sitting in that hammock at that Airbnb in Silverlake…

Dylan Tupper Rupert: Oh yeah.

JH: And I said, “I think we gotta make something out of this.” And we were like, “Is it a book? Is this a TV series? Is this a documentary?” And I don't ever think until we were really both a little bit more ensconced in the world of podcasts did we think, “It's a podcast.” I mean, we baked this idea for solid couple of years: getting together materials, trying to talk about what we were finding in other histories, other big holes. And just thinking about: “what was really the best way to tell this story?” We eventually landed on [the idea that] it needs to be a podcast. We want to hear their voices. We want to hear them tell their story. And so I think the idea of moving beyond a book or something happened once we established, like, “Who are they now?”

DTR: I think a big reason we decided on the podcast treatment was, like Jessica said, hearing the stories. That's what they have, that's what they were able to take away from this time. They didn't become rich and famous. Pamela [Des Barres] became a best-selling author, but she's not living in luxury by any means. And so they came away with this richness of story that we could best tell over, I guess, seven-ish total hours of documentary versus trying to do a 90-minute feature doc or something. We figured out that we needed to have a lens and a scope, and that's where the Sunset Strip parameters came in.

JH: We really wanted to make a thing that was really true to our shared vision of it. We really wanted something that centered them.

I think it was Lori Mattix who said in your podcast that she had been included in 37 rock books over the years. But I am hard-pressed to think of one that really centers her voice.

DTR: Ding, ding, ding. Just on the Lori Mattix tip, of all of these women, she has the most distinct path, in that our other characters hear the siren call of rock and roll and they're going there to try and figure it out. But her narrative, the way she tells it, is different — like, she was swept up, she was chosen to be who she ended up becoming. And that narrative…takes a lot of her away. Like, “Okay, well, what did you want out of it?”

It’s really potent to hear this in their own words. Especially when it comes to the thorny realities of this time, including the power imbalances and the age discrepancies between some of these women and these rock stars. How did you tackle those knottier parts of this history — did you let the reporting inform the way that you ended up approaching it?

JH: We talked about it at different points: “Who are our experts?” And the thing is that when you do see these women in documentaries, [they] say something, and then you see after it’s like the man that wrote the history of that book is like, “Well, you know…” as if they're not reliable narrators. And so we really did just want to focus on: “We don't need expertise, hand of God style to come in here. These women are their own experts.”

I mean, when they're in these rock books — and, yeah, they're in many of them — the only thing they get asked about, truly, is the intimacies of their relationships with these guys. Or were they dumped by them, or were they in love with them? Their stories are, as we see here, so full of life and humor and ambition and desire and wanting to find a place for themselves in music. A Led Zeppelin book isn’t going to give us a chapter on Lori that tells us the stuff we want to know, as journalists who are always looking for the untold stories of our foremothers and forebears. Some of these folks had real dreams in music, and some of them could enact those dreams. And some of them couldn’t. We felt like that was really important to orient ourselves from their understanding of it.

But obviously, we don't turn a blind eye to it either, because every time in that first episode that Dylan mentioned Lori, we pinpoint her in where she was in her age and her life: “She's in junior high and she's 14.” And you can count it in the first episode, every single time Dylan says that…it’s all the ways that their stories have been told, and even sometimes reclaimed outside of their own narratives, have been forced through the constrictions or the views of others. Or the view of others that if you were a groupie, you were disposable. And I think this show evidences, in every minute of it, these women are anything but disposable, and that these stories are vital—and that actually, you don't really know the history of this scene and the Sunset Strip until you talk to these women, who were front and center for so many historic moments. As all of the episodes of Groupies evidence, we didn't know the real fucking story about any of these women.

DTR: There's the phrase “it was a different time.” I joke about it in the script. There's one way that this is used as a tool, and it's a tool of dismissal. It's usually men saying, “It was a different time,” [meaning] I can’t be judged by the standards of today. But it was also something that I could tell [these women] really wanted me to understand. And not to dismiss or diminish or brush off their stories or what happened, but to truly, journalistically, understand the conditions of the time that they were in. And so that became really important for us to show that it truly was a different time. And let's lay out all of these things, and then show what that really meant for the young female experience in rock music.

JH: That was the number one thing that we actually had to cut. We had so much history that Dylan and Jessica [Calvanico], our research producer, went really, really deep on. Jessica went through the entire archive of the LA Free Press to figure out: How were women accessing abortion at that time? And how did that inform how these women were operating? Could you live independently? Could they get their own apartments? Was that legal? Was that hard?

There are all these small parallel moments. Like finding out the Manson murders were the night that [Jimmy Page first] hooked up with Pamela. And then finding out in another book, by people who were on tour with Led Zeppelin, that [the band] moved out of the Chateau [Marmont] to the Riot House. They literally go from being private to, as Dylan says, being welcomed on the marquee at this other hotel where everything was out in the open. And if they were going to be by the pool…I mean, truly, anybody could get up to the pool.

DTR: And no one can get into the Chateau pool! It's like, these little LA things that then map on to the culture changing and the fear and the paranoia. But they also give us a new theory of relativity, of everything that was happening in Hollywood at that time.

JH: We wound up doing a bunch of research on divorce statistics. At one point we were, like, looking up, “Were a lot of men being drafted, and was that impacting people's access to boys their own age?” I mean, we literally got granular on demographics, about what was changing in Los Angeles. Would it have been something that was in people's brains? Then we talked to people, and they're like, “I was taking my mom's Quaaludes in the parking lot. I did not know that there was a war happening, and I didn't give a fucking shit.” Kid Congo Powers…[was] like “No, Jane Wiedlin [of the Go-Go’s] and I were smoking weed. We weren't talking about who was getting drafted or what happened in Vietnam in 1973. We just wanted to get laid.” We were like, “Okay, this clarifies things for us.”

Every little thing that we found just felt like this piece of this puzzle that was so much bigger and…not even like juicier. It’s gratifying. And it felt like, “Oh, my God, are we putting together pieces of rock history that have never existed?” And we get there, eventually. We don’t get punk without groupies. That’s news to me, a gently aging punk.

Who was your initial entry point into this story?

DTR: Jessica hit up Courtney Love to get in touch with Pamela. And she was like, “I'll give her your number, as long as you don't paint her as a victim.” And we were like, “Yeah, exactly.” We knew for sure we wanted Pamela and Lori. I'll start there. We started the first two episodes with them, because they're the archetypes of these two micro-generations. If you know any groupies, you know these two. And whether or not you know them or not, you know the archetype that they created. And then through their murmurs and recommendations then our further research, we were, like, “Who are other women that we want to talk to?” We found Dee Dee [Keel], and Dee Dee was down to dish. Oh my gosh. And we just loved her, and felt like the complexity of her story had so much to tell us about the time. I read Morgana Welch's book, and I was like, “This might be my favorite groupie memoir.” She’s like the shadow side of Hollywood.

JH: She really is. There was also a book, Let's Spend the Night Together, that Pamela did, that was interviews with groupies. And so we knew parts of people's stories from that. But then we found more through her self-published book, which had been, like, a MySpace blog. I think I found screenshots of it on like, for real, a Geocities site that was dedicated to girls who had been go-go dancers at a club in the very early days of the Strip. I mean, all of us were rabbit-holing this stuff to the Nth degree.

DTR: Literally to the end of the world. Then Jessica came in with a bunch of names of people who I identified later as the “baby punks,” who come in and are, like, looking at and witnessing the groupies. Not only do they give us this other dimension and this other perspective of the story, but they're the connective tissue between the mid to the late ‘70s. That was a revelation for us to piece together. The answers that they gave us about what groupies signified to them make 100% complete sense in my mind. And it's almost as if I've known this all along but had never heard it before.

JH: They're the groupies’ groupies, the punks.

How do you think the term “groupie” itself has evolved, and what does it mean right now?

JH: I think it's one of those things where whether or not it's, like, a slur is kind of in the eye of the beholder, the speaker, or whoever's getting called one, too. As we allude to, whether or not you are a groupie [depends on] whether or not you identify as one. Somebody else doesn't get to call you that. But I don't know the evolution of the term where it is today. I don't know if there's a true groupie culture like there used to be.

DTR: It feels like a word from the past, to me. And I don’t have a moral-victorious read on that where it's like, we evolved past it, or we reclaimed it.

Was there an amazing story that you wish could have made it into the podcast?

DTR: So Dee Dee Keel of the Whisky a Go Go had, like, married the guy from the Stooges’ road crew by this point. And she was pregnant with her second child with him. So she's like, pregnant as fuck upstairs at the Whisky answering her phones, and her and Elmer [Valentine, the Whisky’s co-founder] had booked Patti Smith's first shows in LA — and this is before Horses comes out. So [Patti] comes upstairs and is, like, milling around the office, says hi to Elmer and Dee Dee. And she stops, and she's like, “Oh my God, you're so pregnant.” And she goes down and starts talking to her pregnant belly, and giving the baby advice and stuff about how to make it in the world. And then she stands up and she talks to Dee Dee and she was like, “You are so brave for having a child.” And Patti Smith lifts up her shirt and shows her her stretch marks. And she was like, “I had a baby, and I had to give my baby away. Because I couldn't take this baby on me with this path of life that I was on.” And this was before it was public knowledge that Patti Smith had ever had a child. And we asked Dee Dee—Jessica and I were sitting there—“Was that the only time you ever saw, like, another mom in the rock music business?” And she's like, “Oh, yeah. Of course.”

JH: Yeah. I definitely cried. I've always been looking for my forebears—who are, like, the moms in rock? Because most times, even if you are a mom, it kind of gets buried, or it gets put aside. That was one of the things about Dee Dee's story that I just found so inspiring. But she was so dedicated to her own freedom and interest in music, even as a mom, by saying, “My daughter's going to come with me. She's going to come along on my life.” That she was thinking that way at that time, is, to me, just so incredible and radical. And I'm so glad that I got to both hear that story in the Patti Smith story, but also that we get to bring that story wider.

What do you hope people take away from listening to this podcast?

DTR: Justice for the groupies. Not in a “justice against the men who did them wrong” way. But justice [as] in understanding how integral they were to the development of rock music, not just as people who are witnessing it. But people that were pushing it along and contributing in ways that are hard to quantify, but still so valuable, and such a big part of the pie. How to both hold girls’ desires and cravings for freedom and what they wanted as it butted up against the reality of their times. Being able to look at what they wanted without shame. And without feeling like they're too complicated to understand. That's such a shame. It's a shame to see them with shame. So no shame here.